photo brazil interview

Some months back Brazilian art journalist Roberta Tavares did an interview with me for the Brazilian magazine “PHOTO”, and the editor liked it so much they made it the cover story of their end-of-the-year special issue. Roberta asked some really interesting and complex questions, and I had a great time thinking up interesting and complex answers. Since the feature was published in Portuguese, I won’t post the text of the actual article, but I can post the unabridged email interview, which is quite long, but has some interesting nuggets in it. It’s fairly wide-ranging, referencing everything from improvisational jazz to bad ’80’s haircuts to Australian Aboriginal culture, but it was a really enjoyable intellectual exercise to put it all into words, so I’ll leave it to you, dear reader, to decide how much of it you want to read. Thanks so much to Roberta for her enthusiasm and great ideas, and to Giancarlo Nicoloso and the rest of the staff at Photo Brazil for giving me so much space in their magazine. The title of the article translates roughly as “The Art of Repeating Mistakes”, which I think is just perfect–in an imperfect way, of course! NB: I have made a few edits to the language of the questions to make some of Roberta’s themes a little more clear in English.

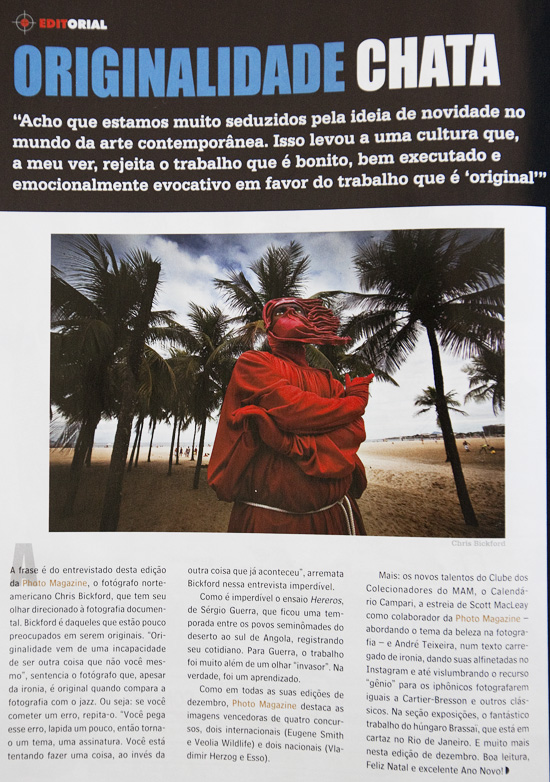

A far as I remember, rituals have seemed to me to be happenings exclusive of different, specific, and often distant people. But through the lens of North American photographer Chris Bickford, ritual becomes something more simple, close, natural, and beautiful to behold. A repetition of patterns, feelings, goals, preparation, commitment, the worship, what to believe in–the repetition that defines a culture, creates common ground and brings individuals together in ways that celebrate both their uniqueness and their bonds with their culture and the whole of humanity. The synthesis of these themes defines Bickford’s body of work in documentary photography. He seeks to re-define and re-discover the ancient idea of celebration and tradition in contemporary examples: the exhuberance of Carnival, the joy and pageantry of weddings, the natural art of surfing, the flirtatious and uninhibited dance of love-seeking youth, and the pilgrimage and mystery of travel.

Rituals are dubious in nature, mysterious and personal…Chris’s interpretations create a narrative that is faithful to the instance, a document not on the celebration, but on the motivation that transcends geography and people. He is always on the lookout for the spiritual urges that motivate us to create and perform these ritual dances with one another and with the world around us.

RT: We could define you as a contemporary documentary photographer. But with your pictures in hand, the artistic content, image processing, color preparation, conceptualism, it’s hard not to identify elements of fine art, a type of photography with potential to please galleries and generates buyers. In this new technological era, there is much discussion around image manipulation programs, but do you think that there might be tools to move the market, to create a more creative and versatile machine, to be out of the ordinary and make people notice you?

CB: Let me see if I can break that down into a few elements. I think the worlds of art photography and documentary photography are starting to merge more and more, and to my mind there’s a lot of room for interesting things to happen there, though by necessity we will still have lines that need to be drawn and rules that need to be followed in terms of journalistic integrity and truth-telling. I don’t think there’s any need, in today’s photographic world, to be an either-or kind of photographer, unless you want to be. Many photo editors are willing to take risks these days in terms of running photos that take artistic liberties–maybe the image is intentionally blurred with a slow shutter speed, maybe it’s shot with a really wide aperture so there is vignetting and a lot of out-of-focus elements. Likewise, many conflict photographers and photojournalists have been showing their work in galleries and selling them as art pieces. So right now the playing field is wide open, and that’s pretty exciting.

As far as new technology goes, there’s a lot of different facets to that question. If you’re talking simply about digital imaging, there’s no doubt that digital has changed the aesthetic of photography. You see a lot of work now that just simply could not be created without Photoshop, and you see a lot of imaging trends, like HDR, sub-saturation, extreme retouching, etc that are hot right now, but it’s anybody’s guess as to what will last and what won’t. Five years ago it was cool to put fake photographic “sloppy borders” around your picture. Now it’s passé. Kind of like hairstyles in movies from the ’80’s. You’d be embarrassed to be seen in public with that kind of hair these days…

So there is a risk, in digital imaging, of going too far with image manipulation, and creating work that might seem really edgy and cool and different right now, but won’t necessarily stand the test of time. At the end of the day, it’s really about the picture itself. You can dress it up in a million different ways, and if you bling it out in a really cool way it might be more attention-getting, but really, it’s still the picture that counts. It’s the moment, the gesture, the expression, the composition. For me, the back-end of playing with color temperatures and dodging and burning and adding contrast and saturation, etc, is all about completing my conception of the picture, bringing out what I see in the image, enhancing the mood I’m trying to convey, and hopefully in the process making the image stronger. I’m not thinking so much about whether or not adding more color or changing the photo to black and white will grab an art buyer’s attention. I’m simply working the picture to make it look the way I myself want it to look. If anything, I sometimes have to tone down my photos before showing them to editors, because some photo editors still think “Photoshop” is a dirty word.

In terms of the new technology and how the internet is changing the world, I find it both exciting and problematic. The exciting thing is that an artist can very much take control of his or her own destiny. Photographers can manufacture their own aesthetic, get really creative with their websites and blogs, try new things…there are just limitless possibilities in terms of creativity, and you can really express your personality online. I’ve really enjoyed all the work that I’ve put into my Travelogue. We spent weeks tweaking out the design of the original pages, and since then it has grown into a very special record of images and recollections. I take a lot of time crafting each post, and each one might take me as much as a few weeks from start to finish. But I only post every couple of months usually, and I really try to make each entry a complete experience, with strong writing and an equally strong set of pictures to accompany. It’s not the way most people use a blog, but for me it works. What I really like about it is that people will literally look through the entire site, click through every picture on the blog, and read every article, in one sitting. They may never look at it again, but the fact that they got so absorbed with it that they spent three or four hours in hang time on my site–I just get a kick out of hearing that from people.

Other people are using blogging and Facebook in other creative ways, whether it be a “picture-a-day” kind of journal–say, for example, with Instagram–or an evolving sketchbook of a long-term project which allows readers a window into their process. There are as many different ways to use the web to showcase photography as there are photographers.

The downside to all this freedom though, is that because social networking has become so popular–and within a period of only a few years has come to dominate the media and communications landscapes–there is this huge frenzy and pressure to make use of those tools for business and self-promotion. Which is great, if you like that kind of thing and are good at it. But it really doesn’t have much to do with how good a photographer you are, and therein lies the problem. You might be really good at self-promotion, and if you are, then you’ll probably do pretty well regardless of your talent as a photographer. But conversely you could be a really great photographer, but have little aptitude or interest in blogging and social media. If so, in the current market, you probably won’t get seen unless someone else takes up your cause. And I think the whole thing can be a huge distraction when you are trying to focus on doing good work.

For me, the biggest problem is that the world of web 2.0 requires CONSTANT updating, which means that if you’re really taking your web presence seriously, you’re updating your blog every day, you’re putting something up on facebook every day, you’re tweeting several times a day, etc….and that’s just way too much being “in touch” for me. I like to disappear, retreat into my own world, or just live my life. It’s enough just keeping up with emails and delivering work to clients and working on assignments, portfolios, etc. The last thing I want to do after spending the day on the computer working is to get on Facebook or Twitter. I’m only speaking out of personal preference here; I realize that this attitude puts me at somewhat of a disadvantage in the current media landscape, but at the end of the day we need to live our lives the way we want to live them, regardless of the opportunities we may miss out on by not living otherwise.

The web is a strange beast; you can get a lot of “exposure” on the web and still not make a lot of money. You can be really popular, and still penniless. Very few media outlets on the web pay any money at all for pictures, and magazine editors that find you by way of the web are usually working for small magazines and also don’t have any budget for photography. So I am still skeptical about it. I think the old systems are still in place, and will continue to be despite the way things are changing. If you want to work for a big magazine, you have to contact the editor, get a meeting, show him or her your work, follow up with emails and phone calls, etc. If you want to have your work shown in a gallery, same thing. Being able to point people towards favorable reviews and articles on the internet is definitely a plus, but it’s a minor convenience. You still have to get in the door, shake somebody’s hand, and show them some real work, preferably on paper. Despite everyone’s calls for the death of print, a printed article is still worth at least ten web articles, because web publishing costs nothing. An editor really has to believe in you to commit one of your images to the expense and logistics of printing; and if you can show that your work has been printed on paper in major publications, you’re going to have a fairly higher status, at least in the business, than somebody who might have a really cool blog. But who knows, things are changing so fast these days, that might not be the case next year.

I hear a lot of people talk about an internet model for print sales, but I think the people that are making good money selling their work on the web are few and far between. I’m not saying it’s not possible, but you’re pretty much running a Mom and Pop shop kind of operation, unless you connect with an agency or cooperative or online gallery or other such entity, and they are going to take half of your money right off the top. If you choose to go it on your own, then you have to build your own infrastructure of marketing, sales, monetary transactions, accounting, packaging, distribution, etc. It becomes a full-time job in and of itself. It’s potentially profitable if you have a popular product, but you can potentially shoot yourself in the foot if you ever intend enter the fine art market. The fine-art market and the popular market are very different beasts. In the popular market, you want to reach as many people as possible, and make as many sales as possible, so you need to price your work at a rate that is affordable to a large number of people. You need to have a marketing vehicle that will reach the masses, and have work that appeals to the general public. The fine-art market tends to eschew populism, and prefers to buy rare, limited-edition work, so you have to price your work high and hope that through making the right connections, getting the proper benedictions from the gate-keepers of the art world, connecting with the right galleries, etc, you can sell your prints for ten thousand dollars or whatever. And additionally, your work needs to be edgy or somehow in line with what is considered “good art” in whatever decade and circles you hope to appeal to.

I can’t claim to be an authority on selling and the art market, because I’m still biding my time until I figure out the best avenue for me personally. My work tends to straddle the line between popular and fine art, so it’s been a bit of a dilemma trying to figure out which way to go. But I do know that I’m better off waiting until I’ve got a better grip on it before I begin a full-out image sales campaign.

In the end it really comes down to plain old business, and being a good salesperson. You can have stellar work, you may have a cool website, you may be blogging and facebooking like crazy, but if you or someone working on your behalf are not aggressively working to sell your images, they won’t sell.

As you can see, it can get pretty maddening just thinking about it, when all you want to do is make a decent living doing what you love.

RT: As a documentary photographer and with your aesthetic concern, your commitment to composition, the ability to capture the decisive moment … that must require such patience, and patience means time, but when time is the hallmark of this new century, in the new advent of communication, where the news comes and tends to be transmitted faster … the time required to capture the right time and from that on, to develop art can also be an aggravating financial factor. Do you try for a beautiful photo instead of ten objective ones that probably the editor would like in the file. Is one great image is enough ?

Oh I’ll go for the one beautiful photo every time! But there is a time and a place and a function for every kind of photography, so it all depends on what is being called for. Sometimes you HAVE to be first; that’s why news is called “news”. I don’t come from a news background, so it kind of took me by surprise the first time I lost a page-one photo on a New York Times assignment because a Reuters photographer got his picture in before I did. The picture the page-one editors ran was a photo anybody could have taken, it was just a picture of a piece of machinery. Meanwhile I had sent them (two hours after the soft deadline, but at least an hour before the hard deadline) this killer picture of the welders working on the thing, with sparks flying and lighting up their helmets, a strong diagonal thrust to the composition, and background stuff too, adding context to the story….but because it was breaking news, they had chosen the first picture that came in over the wire.

Shooting news has always been like that though, and new technology hasn’t really changed anything as far as that’s concerned. If anything, it’s made it easier for photographers to get their photos in on deadline, and it means that everybody in the newsroom can get to bed earlier because they’re not waiting for the film to get developed. Generally speaking most photo editors aren’t speed-freaks. Yes they have deadlines to meet, but the best photo editors are in the positions they are in because they have good taste in photography and they know what makes a strong picture. And most of them have backgrounds working as photographers themselves, so they are sympathetic to the fact that sometimes it takes a little patience to get the right shot.

Sometimes though it’s the opposite, in terms of time. With feature magazines, you might wait an entire year before they run your story. Even in a newspaper, if it’s a feature article or a human interest story that is not time-sensitive, the piece could languish for a month or two before it gets run. If the story can wait, believe me, it will.

Most of my personal work is not really time-sensitive, so I don’t really worry too much about time unless I’m on assignment and under a deadline. And I generally find that if I hang around a REALLY long time, after I think there’s no more good pictures to take, the light is gone, everyone has left the scene, whatever…sometimes literally I am packing up my camera and thinking about food or sleep or something…then suddenly out of nowhere something happens, and bang, you’ve got this amazing picture. Won’t make the front page of next day’s paper, but it might last for years and years as some of your best work. And for me personally, creating work that lasts is more important than making headline news. But like I said, there’s a time and place for both kinds of photography.

RT: You work almost premeditating your themes and subjects, relying on them, that they will not disappoint you and that seems to work out to you.. You display sensitiveness at reading people. Does working this way give you peace of mind ?

CB: Hmm…that’s an interesting question. I’ve never really thought of it in that way. My main attraction to ritual is that it provides a window into the unconscious and the archetypal, but I suppose the other important thing about ritual is that it is habitual, seasonal and premeditated. Rituals are events that generally take a lot of planning and forethought, and their timing is generally something you can set your calendar to. And there is usually a lot of aesthetic work that has already gone into creating the scene –- costumes, lavish ballroom sets, streets decorated, fires and candlelight. But that being said, you’d be amazed how rare it is to see really good pictures of something like Carnival. I think sometimes when people see my Carnival pictures they take the quality of the photos for granted. Like, of course you got great pictures, it’s Carnival, all the world’s a stage. But I’ve got books and books full of the most boring Carnival photos you’ve ever seen. Matter of fact, the only photo book I have of really good Carnival photos is a book by Marco Bertin called “Masquerade”. It’s a phenomenal set of images of the Venetian Carnival scene–a beautiful fantastic world of decadence and sensuality….only thing is, every single photo in the book is staged in a studio, and it wasn't even shot during Carnival. The entire book is a fantasy.

So even though, yes, I gravitate towards subjects that already have a strong built-in aesthetic, that doesn’t guarantee good pictures. The thing is to find the humanity within the artifice, to find the liminal moments when the real and the unreal meet, or when the artifice takes full control and the fantasy becomes the reality…It’s hard to explain, but I know it when I see it.

As for having a sensitivity in reading people, that’s nice of you to say. It’s definitely useful to have as a photographer in any situation. I want people to let their guard down, just a little, but at the same time I do want to see a performance. I like performance; I like drama; I like a heightened sense of reality. But it has to be honest, and it has to come naturally. I can tell when people are faking it or feel uncomfortable, and when they are I usually wait a little longer…sooner or later they get tired of trying to hold in their gut or whatever and they breathe a little sigh, and that’s when the good pictures come.

Everybody is a little different. Some people are born actors and you can see the roles they are playing running through them like a demonic possession. Some people always look worried or angry until the lens gets pointed at them, then they give you their “camera face”…Other people freeze in front of a camera, and those are the people you need to catch unguarded, and sometimes it takes a lot of patience and sensitivity. Often it helps if they are with someone who makes them laugh or whom they feel comfortable with. If they are not, as a photographer you need to become that person.

Photojournalists often talk of trying to capture “non-camera-aware” situations -– which are much rarer than you might think because I can assure you, in this day and age, everybody is aware of cameras. You can see people change their behavior immediately as soon as a camera comes out. And I’m kind of a big guy and I like to shoot wide angle and get close to my subjects. So generally most of my subjects know I’m taking their picture. Usually it’s a simple matter of eye contact and body gesture that lets you in. Sometimes you have to say something, explain yourself, but most of the time if you are in tune with the situation, and carry yourself with confidence and deference, you can get in as close as you want, and answer the “what is this for” questions after you’ve gotten the picture. Unless you’re planning on spending a lot of time with the subjects you’re shooting, or you want them to take you somewhere, or they are providing you with a gateway into other picture opportunities, too much explanation and permission-seeking beforehand is going to ruin the moment. So getting in quick and getting the picture you see before the moment is gone is paramount. You can exchange cards and buy them a beer or whatever afterwards….or you can just disappear into the crowd. I don’t feel it’s necessary always to be a perfect gentleman when it comes to getting pictures. Most of the time it’s good to be polite. But not always.

As for peace of mind, I can’t really say that being a photographer is very conducive to peace of mind, ever. I wish it were different, because I’m a really big fan of peace. But I think most photographers’ minds are crazy, scary places, overflowing with half-baked ideas and philosophical wonder and social concern and to-do lists and deadlines and unfinished projects. That’s just the way it is. You learn to live with it.

RT:. Documenting events that have so many repetitive themes and are covered by so many other photographers can run the risk of either getting dull or degenerating into cliché. What does it take to be original , to have a signature and an agenda filled in with clients?

CB: I’m not overly concerned with being original. It’s not that I don’t recognize the importance of it, it’s just that I don’t think originality should be the primary intent when one sets out to create something. I think we are too much in love with the idea of new-ness in the contemporary world, and it has led to a culture that, to my mind, dismisses work that is beautiful, well-executed, and emotionally evocative, in favor of work that is “original”. Focusing on that which is new or somehow unprecedented removes us from our visceral response to an image, and over-intellectualizes the artistic instinct.

That being said, there are plenty of artists that strived to challenge the artistic conventions of their day and created great art in the process. The French Impressionists. Picasso. James Joyce. Hemingway. But these artists practiced their craft in an age where there were still artistic conventions to challenge. In the contemporary world, most of the classical rules of art are considered irrelevant, and the focus is more on being innovative, or ironic, or hip, or different, or edgy. And so we are at a strange place where being different, being “eclectic”, or being “edgy”, is a cliché in and of itself.

True originality, I think, comes from an inability to be anything other than yourself. I sometimes joke that what makes my work my own is that my imitations of other people’s work are so poor. But I don’t really mean it as a joke. It’s like they say in jazz, if you make a mistake, repeat it. Because it’s your mistake, and you own it. The way you make mistakes is, in essence, the way that you differentiate yourself from “perfection”, which is predictable and boring and soulless. Think of Frank Sinatra. He always sang a little flat of the note. His pitch was not perfect by any means. Yet he turned that limitation into a signature style that even today is admired and imitated the world over. So really, originality comes from making mistakes. You catch that mistake in your hands, finesse it a little bit, then it becomes a theme, a signature, and it’s something that you pulled out of the ether—you were trying to do one thing, but instead something else happened. And it’s that “something else” that makes for the magic.

Some of my best photos are mistakes. I guess that’s the thing, is that if you’re not afraid to fail, then you’ll undoubtedly come up with original work, because it’s the grace with which you fail that defines you, both as a person and as an artist. Originality, to my mind, is just a by-product of the process.

RT: Professional photographers are more than the hands pressing the shutter , they are creative minds. You are also a musician, composer, designer, does it interferes with the way you see photography … does it create more closeness and depth in your work ?

CB: I think it just gives you a lot of different ways of experiencing, interpreting, and expressing things. Being a musician helps, I guess, in terms of seeing the “music” in a particular scene, or creating rhythm in a photograph or photographic series. To me being a writer, a photographer, a musician, it’s all related. You can be creative in a million different ways, but if you want to be a professional then you generally have to pick an established medium to ply your trade in, and if you’re smart you’ll pick the one you’re best at and keep the others as hobbies. But all those other ways of tapping into the sources of creativity give you a broader palette to draw from when you are working in your professional métier. For instance I’m a pretty crappy surfer and never in a million years could I be a professional surfer, but having the experience of surfing is in some ways essential to the way I approach photography. You see an opportunity beginning to develop somewhere out on the horizon, you race like hell to put yourself in the right position at the right moment, and once you’re locked in, you ride it as hard as you can until it fizzles or you have to kick out because there’s danger ahead. I know some phenomenal pro surfers who play music…they’ll never be rock stars, but I know that their connection to music and their connection to surfing come from the same source and inform each other. I think if you were to poll every musician, photographer, painter, actor, dancer, singer, or writer you could find, you’d be surprised how many of them would be fairly well accomplished in another art form as well.

I also find that reading helps me a lot in getting a deeper understanding of things, or just getting a deeper understanding of myself. It makes a huge difference in my work; whether it be in order to understand the historical and social context of the cultures and places I am photographing, or in order to have greater access to the imaginative world. A lot of my work is about imagination, so I pay a lot of attention to my dreams, I’ll let my mind wander into flights of fancy, I’ll read things just because they turn me on in an imaginative way. For me, all of that is part of a larger search for meaning. I think for many photographers, it’s the same. We’re out there in the world with our cameras because we want to understand things, we want to find out about something. For some, that search for understanding is more about social contexts, gender roles, race, identity, conflict and war, what have you. For me it’s about the presence and experience of the sublime in the everyday world; it’s about hearing the music of life, seeing the poetry. It’s about trying to ride the edges between the material world and whatever it is that lies beyond the limits of our abilities to perceive and communicate. I know that might sound a little new-age, and I don’t mean to suggest that every photo I take is about dreams and liminality. But it’s definitely a predominant theme in the life of my mind, and I think it informs the way I see things, and it shows up in the best of my pictures.

In traditional Australian Aboriginal culture, there really wasn’t a concept of time as we know it. There was only the here-and-now, and the Dreaming. And the Dreaming existed side-by-side with the here-and-now, separated by a very thin veil which was permeable through song, dance, ritual, and story. To me, there’s probably no better conceptualization of reality than the way the Aboriginals had it figured. Because when you think about it, what is the past but a memory, which is kind of like a dream; and what is the future, but a fantasy, which is definitely a dream. And the only way to access the past or the future is to “dream” it. You can’t touch it. So for the Aboriginals, the world was imbued with all kinds of magic that they were constantly tapping into, and their entire lives were animated by this duality of the seen and the unseen, of this world and the otherworld, of the here-and-now and the Dreaming. When you start to conceive of the world in this way, reality takes on all kinds of different layers of meaning, and simple objects or moments can become imbued with all sorts of numinosity.

There was an English writer named Bruce Chatwin who traveled to Australia because he had heard about the Aboriginal Song-lines and he was fascinated by the idea and wanted to learn more. Basically, the Song-lines are pathways across Australia that were mapped out in song by the Aboriginals. By learning a song, which generally meant also learning some new dance moves and sometimes even learning a new language, an Aboriginal would be initiated into a new place. The song would recount ancient legends of their animal ancestors, while in the process tell where the singer could find water and food in the area, what kind of hunting practices would be most effective, and what sacred places must be visited and what songs must be sung in order to keep the world alive. The songlines were pretty much containers for the entirety of Aboriginal culture and identity, written on the land, and sung into existence every day by the people.

Now this is a very simplified explanation of songlines and Aboriginal culture, and might seem a little tangential to the question, but one of the most interesting ideas in Chatwin’s book is that, according to one Aboriginal elder, every song-line has a particular “smell” to it. This “scrambling of the senses”, describing space and sound through the medium of scent, is commonly known as synesthesia, and is a common thread in many descriptions of states of ecstasy and higher consciousness…we hear colors, see music, smell poetry, taste beauty. To me, it is this kind of all-encompassing experience that great art aspires to, and I think it is why the arts so often bleed into one another.

So that’s a very long-winded answer to the question, but my point is that what we are getting at in all this art-making–in our songs, our pictures, our poetry, our dances—is an experience that moves between and beyond the five senses, but we have only the limited palettes of our artistic media to use as pathways into this larger thing. I think that’s why you find that so many artists experiment with other branches of the arts. It’s like adding one more dimension to something that is ultimately ineffable, but with just a little more knowledge, we can understand and express just a little bit more about it.

RT:. Which is more difficult: exceptional photos of surfing or an original photograph that captures the struggling of areas after disasters like the ones you brought from Haiti ?

CB: Well, they each have their challenges, but if I were hard pressed to answer either/or to that, I’d have to say working in Haiti is much harder. In a place like Haiti, there is so much suffering and destruction, and so many people everywhere you look, that it gets to be overwhelming. And at the same time that your heart bleeds for the people and their situation, your mind is racing and your guard is up, because you know that you stick out like a sore thumb, you don’t speak Kreyol, and you don’t want to get into a dangerous situation. You’re also very aware of the sheer complexity and near-hopelessness of the situation, and that can make you lose heart, which you absolutely don’t want to do because if you don’t go into something like that with some sense of hope that something can change for the better, then you’re basically a pornographer of disaster -– that, or you’re just looking for the paycheck, the byline, and a new stamp on your passport. It’s really tough to remain sensitive to the situation and be in photographer mode at the same time. When I was in Haiti I was shooting a lot from the hip and not taking a lot of time to work any particular shot or situation, because after about three or four clicks of the shutter at any given moment, you become a paparazzo, a voyeur, and for the most part the Haitians, like any self-respecting people, do not appreciate being photographed by drive-by journalists who want to get a picture of somebody forced to shower naked in the street because their home got destroyed in the earthquake. So the best you can do is just be there and take it all in, talk to anyone you can communicate with, and hope that when you get home there are three or four grab shots that mean something, and can convey a sense of what it is like there without making it just seem like hell on Earth, which is what I used to think of Haiti before I went. Now that I’ve been there and made some friends, it has taken on a greater sense of reality. You see the hope and potential amidst all the rubble and you think, man, if only there could be a happy ending here. There is so much spirit and heart and soul in Haiti, but everybody’s so mired in the latest disaster that they can’t catch their breath long enough to move forward. So for me, I think the best response as a photographer in that kind of situation is, and I know this is going to sound corny but I’m going to say it anyway, shoot with your heart and forget about “getting the shot”.

As for the surfing stuff, I only shoot surfing in one place, my home on the Outer Banks. In some ways it’s kind of the direct opposite of something like Haiti. My home is a very laid-back beach, and we don’t have massive insurmountable social problems. People are here because they choose to be here, and there’s not much big change that happens around here. So I’m not tackling any big headline news stories or grand social issues. The work is more about conveying a sense of this wild and windswept chain of sand dunes and this crazy sport that is more like a dance with the gods than any other human pursuit I know of. Thematically it’s about the experience of the most raw and elemental forces of nature–sun, wind, rain, sand, storms, waves, etc–and how the surfing community on the Outer Banks, through the peculiar geography of the place, is especially close to that experience. For me it’s a very immersive project–literally–because I am sitting out there in the impact zone with a pair of swim fins and a camera getting tossed around by the surf. It can be physically challenging when the surf is high, and it can be frustrating sometimes because sometimes months can go by without a single decent picture…and sometimes I miss really good opportunities to shoot because I have other work or I’m out of town. And trying to document something that you like to do yourself, you are always presented with a dilemma: surf or take pictures?

If you only have a week, which is all the time I had in Haiti, you can come up with a lot more images in Haiti than on the Outer Banks. Things are less concentrated here, time is a bit slower, sometimes nothing is happening at all. So it requires a lot of patience. In Haiti, there’s always something happening, always people, always some kind of picture. Still, at the end of the day, shooting in Haiti is a constant challenge and a major heartbreak, while shooting on the Outer Banks is just a hell of a lot of fun, but it requires time and patience.

RT: You have photographed and participated in Carnival celebrations in Venice, Brazil, New Orleans. How was to lead this project and to make them evoke some idea of similarity…but to avoid the idea of being the same thing ?

CB: It started off just on a whim one winter when I was having romantic troubles and decided a trip to Europe might give me some perspective. A week later I was in Venice during Carnival, and I got totally caught up in it, and from there the thing just grew. But I think the seed of the whole project actually was sown a year or so before that, from a sidebar that I saw in The New York Times Travel section, where they did a very short listing of the four great Carnival celebrations as they saw them: Venice, New Orleans, Rio, and Port of Spain in Trinidad. I just had that tucked away in my mind somewhere, and somehow it stayed with me. To me it was interesting that this ancient celebration, with the same name, occurring at the same time of the year, had migrated from Europe and flourished in all these other places. And what has been so interesting about the project is how strongly each Carnival represents the culture of the cities they take place in. The Venetian Carnival is all mystery and artifice, very classical and full of fantasy and secrets. There are masquerade balls in ancient palaces and ancient ceremonies and parades. The New Orleans Carnival has is a lot of racial and social differentiation, and each social and ethnic group in New Orleans has its own Carnival–there’s a gay Carnival, an “old-line” upper-crust Carnival, a working class “Carnival Noir” with the Mardi Gras Indians and other cultural icons of black New Orleans; there’s a bohemian Carnival scene, “marching societies” mainly made up of working-class men’s groups….there are women’s krewes and “superkrewes”–it’s a very funky, American melting-pot kind of celebration… The Carnival in Rio is, hands down, the sexiest of them all–no surprise there–and I don’t think any other Carnival anywhere can match the incredibly elaborate performances that the samba schools put on in the Sambadrome. But the Sambadrome, for all of its beauty, is pretty much like watching a spectator sport, and Carnival is, in its original spirit, a participatory event, so it’s cool to see that the blocos and bandas are bringing Carnival back to the streets. In Rio, people really are DANCING in the streets, moreso than at any other Carnival I’ve been to…

So it’s been great fun exploring the character of three of the most interesting cities in the world from the point of view of their Carnival celebrations, because it’s during Carnival that they show their colors if you will—you get kind of a heightened sense of reality and a glimpse into the soul of the city, because they are putting themselves on display, creating their own city-wide communal art project. It’s really quite a special thing, when you think about it. And the amazing thing is that the locals never tire of it–at least in Rio and New Orleans. On the contrary, they LIVE for Carnival. In Venice it’s a little different, since the modern Carnival in Venice is only 30 years old–it was banned way back in the 1800’s by the occupying Austrian government–and so most of the locals still don’t see it as a real indigenous part of their culture, but more of a spectacle to increase winter tourism. That being said, those at the vanguard of creating the new Carnival in Venice couldn’t be more on the mark in expressing the soul of the city, which is a glorious achievement, because they really had to start from scratch when they were reviving Carnival in the ’80’s.

But on a deeper level, there is something about the very concept of Carnival that I find endlessly engaging, and which I could take a lifetime to explore in pictures. I think it taps into a very deep part of the human psyche that wants to lose itself in a stream of what writer Barbara Ehrenreich calls “Collective Joy”. In her book “Dancing in the Streets”, she discusses the history of the Carnival spirit, tracing it way back into prehistory, where communal dancing and singing served as a “technique of ecstasy” and made it possible for large groups of people to live together in relative harmony by way of rituals which allowed them to merge their individual beings into a single writhing, entranced, spirit-possessed organism. As she traces the various forms this kind of ritual has taken throughout history, she comments, “the core elements are, again and again, the dancing, the feasting, the artistic decoration of faces and bodies.”

So here we have, in the twenty-first century, every year, in the days preceeding Lent, tens of millions of people around the world–in Venice, Rio, New Orleans, Port-of-Spain, Salvador, Recife, rural Louisiana, Switzerland, Germany, France, Alabama, Spain, Peru, Haiti, Bulgaria, Romania–all engaged in these ancient rites of collective joy. Painting their bodies and faces, dancing, drinking, feasting, making love. And though some will decry the commercialism of this or that Carnival celebration–though I assure you there’s not much commercialism going on in Mamou or Bulgaria–the essential thing is that there persists, even into this most modern era, an urge within the collective human consciousness to put on a mask, walk out on to the street, dance and sing and make love with strangers, and generally drop all taboos and norms for a few days of wild Bacchanalian revelry. And unlike a rave or a nightclub, this is a celebration that is for young and old alike, that reaches deep into history for its particular cultural expressions, and speaks ultimately to a kind of religious need within us to experience something otherworldly alongside our human brethren.

What is so engaging about it as a photographic project is that each new place is like a folksong you knew in a different language, and it had a slightly different melody, but you still know it’s the same song. I already know what the basic pattern is; I’ve danced in the streets and palaces of Venice, Rio, and New Orleans with Mardi Gras Indians, Harlequins, Samba Queens, nuns, ballerinas, vampires and sailors…. So every new Carnival, even though different, seems familiar to me. And tracing the patterns, noting how each culture uses variations of the same basic elements to create their own cultural identity….it’s just a trip. Such a trip.

RT: The flirting, the women’ sensuality, libido, the nature of desire … Is this the primordial ritual that will ever inspire more attention ? is the reason you hence emphasis on these elements ?

CB: Leave it to a Brazilian woman to ask a question like that!! I guess to some extent that’s true. The dance of love is definitely one of the oldest and most primordial…and it is, literally, the thing that ties us all together. Every single one of us came to be because two people did the bumpidy-bump…it’s the essence of human creation….So yeah, that’s definitely an aspect of my work, although it’s more suggested than anything else. It’s not like I’m taking pictures of people having sex.

It’s funny though, at a show I did recently there was a woman who worked in the gallery who objected to some of the sexier photos in the exhibition. She said she was a Christian, and such imagery offended her. To my mind that’s very telling of a major disconnect in our society, because the way I see it, sexual practice at least has the potential to be one of the most sacred acts human beings can participate in. The Hindu Tantrics knew this, as did many other pre-Christian religions. Instead, we have politicized, commodified, commercialized, trafficked, and exploited sex in just about every way possible. So I don’t blame anybody who objects to sexual imagery. It’s a very thorny issue, because as humans we are complex, selfish, imperfect, and ruled by our desires, and sex can be a very violent and destructive beast, which is why different makers of “law” have almost always sought to regulate or forbid it. But you might as well try to stop a hurricane.

It’s important to remember, however, that while sexuality is without question a huge primordial force, and probably the most significant creative act that human beings can participate in, there are much more ancient, more primordial forces at work in the world. The sun, the moon, the wind and rain, the movements of the stars and planets, the roar of the ocean, earthquakes and typhoons, the march of the seasons and the bounty of plant and animal life…The thrust and parry of two sweaty human bodies is but a blip on the radar of the great primordial dance of the cosmos….remember that next time you get dumped by your lover.

But that being said, for us, sexuality can serve as a portal to participating in the greater forces of creation that animate our lives. In Greek mythology, all of existence flowed from the coupling of Uranus and Gaia, heaven and earth, which in some ways could be interpreted as the original sexual act, and perhaps the great wonder of human sexuality is that it allows us to participate in this archetypal marriage of heaven and earth, to experience some small shred of the original orgasm, the “big bang” if you will pardon the pun (which probably doesn’t translate well into Portuguese anyway), that released the energy that set creation in motion…

And yet so often we approach our sexuality in the most petty, small-minded ways, obsessing over physical appearances and wrapping up so many personal and psychological issues into the sexual act. We have come so far, in science, in medicine, in technology, in psychology–and yet at the same time we have strayed further and further from direct experience of the sensual, and further and further from direct communion with the sources of creation. It’s ironic in some way, that with the rest of our sensual experience being atrophied by the conditions of modern life, we are left only with the sexual act as our primary universal means of dancing with creation…and yet rather than protect it and sanctify it, what do we do? We commercialize it, trivialize it, forbid it, pornograph it, buy and sell it, torture teenagers and mid-lifers alike with insecurities about it…it all seems so sad, when if there’s one thing that every person should have, after food and shelter and loving parents, it is a satisfying, fulfilling, meaningful sex life. But so few of us get to have that, get to really have it.

Which I guess is another reason why it is so endlessly fascinating a subject to explore.

RT: First, you strengthened the rhythm of your pictures: sensuality, defining moment, focus, mystery…but you have also developed certain techniques, such as your use of flash, and have been recognized for your skills with it. Would that be your secret weapon, to know how to use deliberately this artifice ?

CB: Well it helps to bring the right tools to the job, and it helps even better if you know how to use them! I’m honestly not very technical about my work; I know just enough to get by, and I kind of fake the rest. I do like to mess around with things though, whether it be different colored gels on my flash, or tweaking color temperature settings once I have my photos into the computer. But the whole process is pretty loose, and is kind of an endless feedback loop: you try out certain techniques, and if the results excite you, you keep moving in that direction. Then, maybe you start to think you are over-using a certain technique, so on your next project you try to change things up a little bit.

I figure I still have a lot to learn in photography, and there are a lot of things I still want to explore. There’s so much more I’d like to do with lighting, and even more I want to play with in terms of perspective and composition. I’ve got a list a mile long of different projects I’d like to do, very few of which would ever make it into a magazine article, so they’ll either have to become huge book projects or just little web essays. I’m also interested in working with tilt/shift lenses, not to get that kind of “toy village” look that’s in vogue right now, but to get really dramatic architectural photos with wide angles, and to add people into that mix for added intrigue.

At the same time, I’ve always wanted to ride across Europe with nothing but an old Leica and a bunch of store-bought film, a single 35 mm lens, and no real agenda. No flash tricks, no crazy angles, just take off on an adventure with a little camera and see what happens. Get back to basics, if you will.

I think the great “secret” is to never stop trying to learn and grow. At least that’s the way I’m looking at it.